Can I sing over G.711?

Table Of Contents

Me? “No!” Simply because I’m a terrible singer… But the technical answer is actually “Yes, you can!” And that’s what makes this question fascinating.

Recently, while preparing training material on troubleshooting audio and network issues, I’ve learned that understanding the fundamentals is crucial. The relationship between human voice, audio codecs, and network behavior forms the foundation of modern communication systems.

Think about it: every day, millions of people make phone calls, participate in video conferences, or even collaborate on remote music projects. But have you ever wondered how your voice travels through the digital maze of networks and still sounds (mostly) like you on the other end?

This journey of understanding starts with two key elements: how we produce and perceive sound, and how codecs affect our voice.

Let’s dive into this fascinating world of audio communication, and I’ll show you why even my questionable singing abilities can technically make it through a G.711 codec!

Troubleshooting Audio Issues

When users complain about audio quality, the natural reflex is often to blame the network. While this is often true, the network isn’t always the culprit for poor calls.

Here are the most common audio issues we encounter:

Noise level: The sound isn’t loud enough. This typically relates to microphone or speaker settings, or to application-specific gain controls.

Echo: Regular or amplified sound feedback loop between speakers and microphone. This usually stems from application settings or usage scenarios (like multiple people in the same room).

Choppy or robotic voice: When it becomes painful to understand your conversation partner. This typically indicates network issues like packet loss or jitter.

One-way audio or white call: These are signs of network issues (signaling works but media flows are blocked): Often due to network segregation between signaling and media paths, VLAN configurations, NAT problems, or firewall restrictions.

Call cuts after a while: Often around 30 seconds, usually related to network timeouts or security policies.

Late audio on start: A frustrating issue where there’s no audio for several seconds at the beginning of the call. This often leads to call termination by impatient recipients who think the connection failed. Interestingly, even chrome-internals might not show any concerning metrics…

Understanding how voice is processed and transmitted is crucial for effective troubleshooting and distinguishing between network-related issues and other problems.

The Voice Processing Chain

When calling someone, the voice travels through multiple transformations before reaching the listener:

The Capture

- Not all voice characteristics are equals: Frequency, amplitude and sound level, all have an influence

- Microphone quality (Condenser, Dynamic), connectivity(XLR versus USB) and positioning play a major role

- Background noise and acoustics: the surrounding environment may impact

The Encoding

- Sampling rate, bit depth, channels: how the signal is digitalized

- Codec efficiency: From fixed bitrate to adaptative bitrate codec, the width of the frequency spectrum captured

- Buffer sizes and processing delays: Exist but low impact

The Network Transport

- This is how packets transmission and ordering impact the decoding

- Packets can be corrupted, lost or delayed

The Decoding

- Unpacketization

- Concealment of missing packets

- Sampling voice

The playback:

- Again the speaker quality and positioning may impact

- The route to the speaker may introduce additional delay

- Room acoustics

- Human hearing limitations

Understanding Voice

Voice is a complex acoustic signal produced by the coordinated action of our vocal system. It’s created when air from our lungs passes through the vocal cords (or vocal folds), causing them to vibrate, and is then shaped by our vocal tract (throat, mouth, and nasal cavities).

The Frequency is one of the characteristics of sound (along with intensity and duration) and indicates the number of vibrations per second expressed in Hertz (Hz). A low frequency produces a low-pitched sound, while a higher frequency produces a high-pitched sound.

The Physics of Voice Production

The air pressure from lungs creates the power source. Then the vocal cords vibrate to produce the fundamental frequency. This vibration creates a buzzing sound (the source) including harmonics.

What make our voice unique, is that different shapes of mouth, tongue position create different sounds and resonances called formants. These formants give voice its distinctive qualities.

The human voice consists of several key components:

The Fundamental Frequency (F0): This is thee lowest frequency of vocal cord vibration. It determines the perceived pitch of the voice and it varies by gender, age, and individual physiology.

The Harmonics: Harmonics are multiples of the fundamental frequency. Harmonics create the richness and timbre of voice. They usually extend up to 8-10 kHz in speech.

The Formants: They are the resonant frequencies of the vocal tract. Usually 3-5 main formants in speech. They are critical for vowel distinction and voice recognition.

Voice Characteristics

Different aspects of voice can be identified (measured) and analyzed:

The Pitch: The speaking pitch varies during speech. This is call the prosody. For an adult male, the fundamental frequency average speaking pitch ranges is 100-150 Hz. For adult females, it is 170-220 Hz and for children: 200-300 Hz.

The Intensity: Intensity is measured in decibels (dB). A normal conversation is around 60-70 dB. Whispering is about 30-40 dB and shouting is over 80-90 dB.

Other factors: Other things such as the timbre (voice color), the resonance…

The language is another thing that shapes the sound.

Voice frequencies

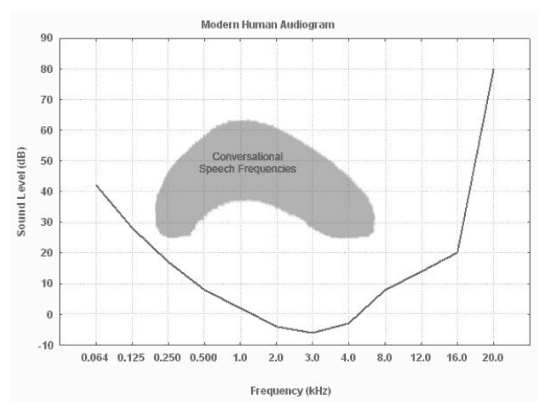

Here is a representation of a human audiogram which represents the frequency range of conversation-level human spoken language (shaped region). It was published in ”From Studying audition in fossil hominins: A new approach to the evolution of language?” - 2012

The line represents the minimum audible threshold as a function of frequency. This is the minimum sound level at a given frequency which a human subject can correctly perceive at least 50% of the time. Points lower on the curve indicate a greater auditory sensitivity, and the best frequency appears to be around 3 kHz.

But conversational frequencies vary from around 200 Hz to 4 kH as shown in the shaded region. And what shows this diagram is that people with a deep voice are harder to hear if their voice has a low intensity..

This representation is also called the Speech Banana. It is used in pediatric: While many other sounds fall outside of the speech banana, audiologists are most concerned with the frequencies within the speech banana because a hearing loss in those frequencies can affect a child’s ability to learn language.

Frequencies and Harmonics

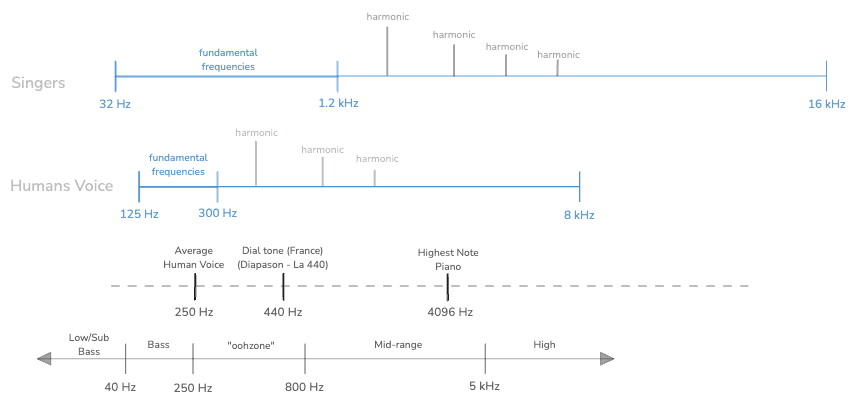

Here is a diagram that summarizes the range frequencies for the Human voice.

There are 2 things to differenciate: The fundamental frequency and the human speech or conversational speech.

The human voice average (fundamental frequency) is around 250 Hz. But when speaking and depending on the language used, this fundamental frequency may vary from 125 Hz to 300 Hz. For singer such as a soprano,the frequency can go up to 1 kHz.

But when we speak, we “modulate” the fundamental frequency and so the range is from around 250 Hz to 8kHz. This represents the full frequencies range of Human speech sounds including vowels and consonants (higher frequency). This wider range is needed for a clear and intelligible speech.

This includes harmonics. Harmonics are frequencies that are integer multiples of the fundamental frequency (F0). Thanks to harmonics, we perceive the speech in a richer and more natural-sounding voice. When listen to a singer, we can hear sound up to 16 kHz thanks to harmonics.

To note, every harmonic loses around 6 to 12 dB per octave. For example, for a speech at 60 dB in a quiet environment, you may expect several dozens of harmonics up to 6,4 kHz before having too much attenuation.

Even if the fundamental frequency (the lowest harmonic) is absent or weakened, higher harmonics still allow listeners to perceive pitch clearly (so called the missing fundamental effect). It will have an impact in the codec paragraph.

Human sound range

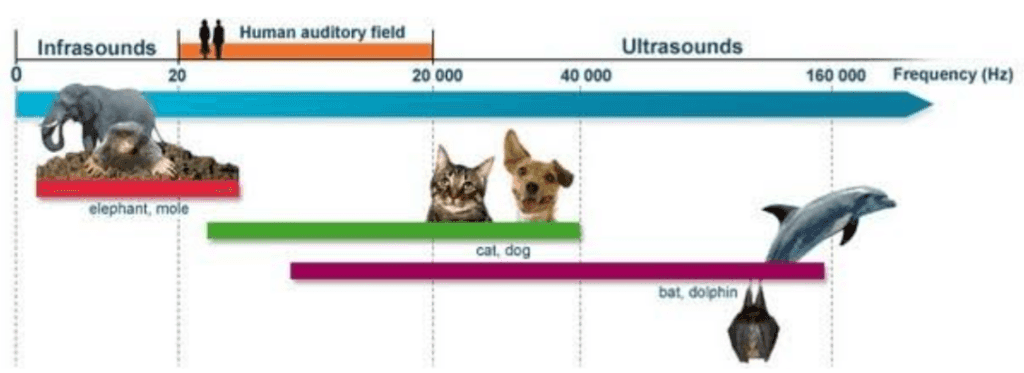

Humans are able to listen sound from a range starting at 20 Hz up to 20 kHz.

This is a very large spectrum but comparing to a cats, dogs, dolphins or elephants, they have ears super-power for high frequencies…

And year after year, we’re losing little by little the capacity to listen to high frequency. That’s why our children are able to hear sound that we can’t :-)

WebRTC Codecs

Time to look at codecs and especially the range of frequencies they are able to capture.

Codecs categories

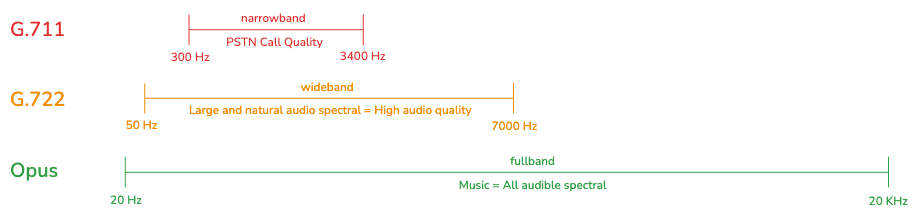

Codecs can be divided into the following categories:

- Narroband (NB) Codecs

- Example: G.711

- Bitrate: 64kbps

- Frequency Range: 300 Hz to 3.4 kHz

- Wideband (WB) Codecs

- Example: G.722

- Bitrate: Typically 64 kbps (can vary)

- Frequency Range: 50 Hz to 7 kHz

- Super-Wideband (SWB) Codecs

- Example: G722.1C

- Bitrate: Typically 24-32 kbps

- Frequency Range: 50 Hz to 14 kHz

- Fullband (FB) Codecs

- Example: Opus

- Bitrate: Variable (6kbps to 510 kbps)

- Frequency Range: 20 Hz to 20 kHz

Codecs frequencies

If we focus on the frequency range, we can see the huge difference between G.711 and Opus in term of the audio spectrum captured.

Compared to Opus, G.711 seems not to be able to capture people having a very deep voice and people having a high pitched voice. We will discuss the point after.

It seems to be confirmed by our “speech banana”. Some part of the dashed area are not covered by G.711.

G.722 is far better. Here, the codec captures a broader range of frequencies, including some harmonics which allows a better voice quality and cliary than narrowband.

And then Opus, which covers the entire human hearing range. This provides the possibility to have an enhanced audio experience and to cover music in high fidelity.

Practical test with Céline Dion

To move from theory to practice, I conducted a real experiment using a high-quality recording of Céline Dion: “All by Myself”. Here’s how I set up the test:

Test Setup

Source Material:

- Purchased a high-quality WAV file from Qobuz

- Selected a song with both high and low vocal ranges to test frequency limits

- Original recording quality: 16-bit, 44.1 kHz, lossless

Test Environment:

- Created a web-based testing application using WebRTC

- Implemented two peer connections for comparison testing

- Set up real-time audio visualization using Web Audio API and display the graph of the original audio and the received audio

Test Scenarios:

- Reference: Direct playback (reference)

- Scenario 1: Opus codec transmission

- Scenario 2: G.722 codec transmission

- Scenario 3: G.711 codec transmission

- Scenario 4: Generate test tone from 150 Hz upt to 4kHz

Implementation Details

The first step is to get the audio from the Wav file

// Create audio context and sourceconst context = new AudioContext();const audio = new Audio("./celine.wav");audio.crossOrigin = "anonymous"const track = context.createMediaElementSource(audio);// Add a gain nodeconst gainNode = context.createGain();gainNode.gain.value = 0.2;// Connect the audio pipelineconst mediaStreamDestination = context.createMediaStreamDestination();track.connect(gainNode).connect(mediaStreamDestination);// Get the input streamconst mediaStream = mediaStreamDestination.stream;audio.play().then(() => {console.log("playing");}).catch(err => {console.log("error when playing sound", err);});

The second part will be to select the appropriate codec for the negotiation with the remote peer

function setCodecPreference(transceiver, codecType) {if (RTCRtpSender.getCapabilities && RTCRtpSender.getCapabilities('audio')) {// Retrieve the list of available codecconst capabilities = RTCRtpSender.getCapabilities('audio');let codecPreferences;switch(codecType) {case 'g711':codecPreferences = capabilities.codecs.filter(codec =>codec.mimeType.toLowerCase() === 'audio/pcma');break;case 'opus':codecPreferences = capabilities.codecs.filter(codec =>codec.mimeType.toLowerCase() === 'audio/opus');break;case 'g722':codecPreferences = capabilities.codecs.filter(codec =>codec.mimeType.toLowerCase() === 'audio/g722');break;}// If codec availableif (codecPreferences.length > 0 && transceiver.setCodecPreferences) {transceiver.setCodecPreferences(codecPreferences);} else {console.warn(`Can't change default codec`);}}}// From the input stream, put the audio track to the peer-connectionmediaStream.getTracks().forEach(track => {const transceiver = pc1.addTransceiver(track, {streams: [stream],direction: 'sendonly'});setCodecPreference(transceiver, currentCodecPreference);

Then to play the received sound

<audio id="player" autoplay></audio><canvas id="canvas-receiver"></canvas>

const player = document.querySelector('#player');pc2.ontrack = async (event) => {// Connect the stream received to the audio playedconst streams = event.streams;player.srcObject = streams[0];

And finally to analyze the received sound

// Manage the Canvas (frequency bars)const canvasReceiver = document.getElementById("canvas-received");const canvasContextReceiver = canvasReceiver.getContext("2d");// Manage the audio receivedconst contextReceiver = new AudioContext();const analyserReceiver = contextReceiver.createAnalyser();// Create a media stream source from the received streamconst receiverStream = contextReceiver.createMediaStreamSource(streams[0]);// Connect it to the analyzerreceiverStream.connect(analyserReceiver);// Draw the frequency barsdrawFrequencyBars(analyserReceiver, canvasContextReceiver, canvasReceiver, "Audio Received");

The function drawFrequencyBars splits the frequencies into small ranges and displays a bar depending on the magnitude of the signal.

Note: Code is a bit long to be displayed here. Contact me if you need it or ask your prefered AI to generate it :-)

Observations and Analysis

This is what I heard and saw

Your ears adapt to sound quality

Audio quality is one thing, but the emotional response to music is another entirely.

This is perhaps the most important point: if you consistently listen to music at medium quality, you won’t necessarily perceive it as lower quality. You’ll focus on the song, the melody, and the lyrics, essentially forgetting about the technical quality.

It’s only when you compare the same song in high quality that you might notice differences - and even then, not always.

G.711 is not Opus

While the music quality obtained with G.711 seems acceptable, there’s a noticeable difference when using Opus.

With Opus, the sound appears lighter, which makes sense: Opus delivers more high frequencies than G.711.

Remember, G.711 is limited to 3.4 kHz.

However, this limitation isn’t as problematic as it might seem. Most frequencies in Celine Dion’s voice fall below 3.4 kHz. Her fundamental frequencies typically peak around 1 kHz.

Consequently, G.711 captures about 60% to 70% of the voice. The main difference is that G.711 doesn’t capture all harmonics.

The sound through G.711 appears more hollow and harsh compared to Opus, lacking the smoothness of the latter. It has a more piercing quality to it, which is particularly noticeable in higher frequencies.

But as Tsahi observed (see the comment below), prolonged exposure to G.711 audio can be mentally fatiguing: our brains need to work harder to process and distinguish syllables and words since the voice sounds less natural compared to what we’re accustomed to hearing in everyday life.

Some measures

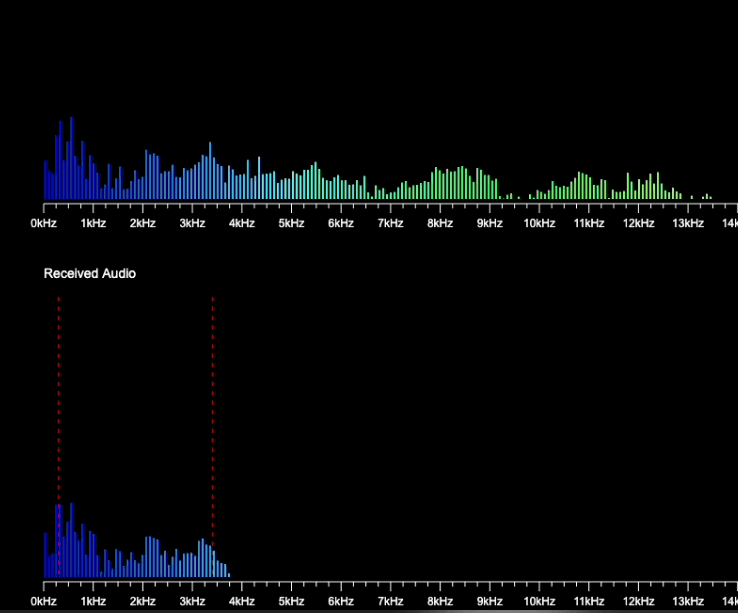

I did some stats over 10 seconds from the source signal and the received sound to compare.

Source Audio:- Frequency Range: 0Hz to 19.5kHz- 0-300Hz: 8.38% energy, 6.92% frequencies- 300Hz-1.5kHz: 23.96% energy, 26.59% frequencies- 1.5kHz-3.4kHz: 24.52% energy, 32.16% frequencies- 3.4kHz-8kHz: 28.48% energy, 28.30% frequencies- Over 8kHz: 14.65% energy, 6.04% frequenciesReceived Audio:- Frequency Range: 0Hz to 3.9kHz- 0-300Hz: 14.62% energy, 10.81% frequencies- 300Hz-1.5kHz: 42.09% energy, 41.65% frequencies- 1.5kHz-3.4kHz: 39.40% energy, 44.51% frequencies- 3.4kHz-8kHz: 3.89% energy, 3.03% frequencies- Over 8kHz: 0.00% energy, 0.00% frequencies

What I observed:

- During this period, G.711 missed around 40% of the original frequencies.

- Despite G.711 captures starting at 300Hz, it seems to have sound played for the range 0-300Hz (around 15%).

- It seems that some frequencies are above the 3.4 limitation (4%)

I can’t explain these observations. It can be a bug in my visualizer (with the way I split the frequencies received) or these frequencies have been preserved or regenerated (from harmonics?).

Here you can check the frequencies analyzer.

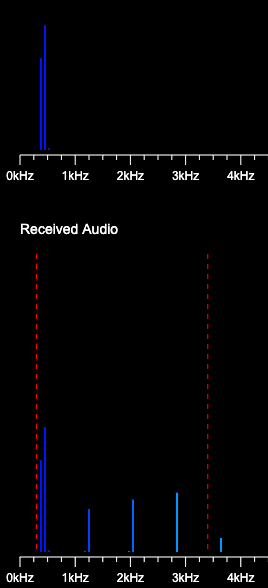

Test tones are removed

To be sure that everything works great, I did a last test.

I generated tones from 100 Hz up to 3.8 kHz to try to see if specific frequencies are kept or not with G.711.

First, don’t try it your self. Pure frequencies over 1.5 kHz (for me) hurt my ears… I tested with a low-intensity sound but above all visually by looking to see if the frequencies were received by the receiver.

context = new AudioContext();// Create oscillator and gain nodesconst oscNode = context.createOscillator();const gainNode = context.createGain();gainNode.gain.value = 0.2;// Prepare the audio pipelineconst mediaStreamDestination = context.createMediaStreamDestination();oscNode.connect(gainNode).connect(mediaStreamDestination);// Start at 100 Hzlet currentFreq = 100;oscNode.frequency.setValueAtTime(currentFreq, context.currentTime);oscNode.start();// Increment frequency by 100 Hz every 2 secondslet testToneInterval = setInterval(() => {currentFreq += 100;if(currentFreq < 3000) {oscNode.frequency.setValueAtTime(currentFreq, context.currentTime);} else {clearInterval(testToneInterval);testToneInterval = null;oscNode.stop();context.close();context = null;}}, 2000);

From the test I did, I was able to hear an audible sound starting 120 Hz, but even with using an oscilator, I saw that sound is not “pure” meaning that from the source I saw a range of frequencies rather than just one value exactly at the frequency asked.

Sometimes, it is the same for the received signal but for example at 400 Hz, I received only very few distinct frequencies which seems to represent the fundamentals and the harmonic frequencies.

For tones generated over 3.8 kHz, I try to hear but it seems that sound seems to be cut. Perhaps not for all frequencies, but as I want to keep my ear, I didn’t test more…

Conclusion

While G.711 won’t deliver studio-quality singing, it’s surprisingly capable for vocal transmission because:

- The fundamental frequencies of most singing voices fall within its range

- The preserved harmonics provide enough information for pitch perception

- Our brains can effectively reconstruct the musical experience

This is why services like traditional telephone lines or legacy PABXs, while not ideal for music, can still effectively carry singing voices and let you sing “Happy Birthday” to someone!

Despite its capabilities, G.711 cannot match the full-spectrum experience that Opus delivers. The limited frequency range makes extended listening sessions less enjoyable, as you miss out on the subtle nuances and rich overtones that make voices sound truly natural.

However, if you’re seeking better quality, Opus is the codec to choose. For real-time communication, it’s currently unmatched, as far as I know.

So, if you want to preserve your distinguished tenor or soprano voice, choose Opus! Fortunately, it’s the default codec used in WebRTC!